History through the decades

The following history of the vocational education and training sector in the NT has been collated and written by Dr Don Zoellner, Research Associate at the Northern Institute, Charles Darwin University.

From missions to the mainstream: the 1950s

At the start of the 1950s, vocational training had long been used by a range of missionaries, relying upon the charitable donations of church-goers, to ‘improve’ the lives of Indigenous Territorians. These endeavours had commenced with the Lutheran mission at Hermannsburg in 1877 (Hart 1970) and this was followed by the Anglican Mission at Roper River in 1908 (Joynt 1918). The Catholic Church was granted land on Bathurst Island in 1910 to establish a mission and would go onto provide training for Indigenous people in a variety of NT locations (Donovan 1983). A number of Methodist missions were established across northeast Arnhem Land commencing with Goulburn Island in 1916 and ending with Elcho Island in the midst of World War Two in 1942 (Baker 2012). These missions shared the view that vocational training would provide the residents with the skills required to participate in a real economy by becoming a competent worker contributing to the newly-established European-style towns. Indigenous leaders were joint partners and advisors in the philanthropically supported development of the labour market, and associated training, for their communities (Baker 2012).

The Commonwealth Government did not involve itself in the provision of vocational training in the Northern Territory until the 1950s (Hart 1970). Even then a number of senior public servants questioned if adult education was ‘absolutely necessary’ in the Territory given the shortage of residential accommodation which should be prioritised for school teachers over trade trainers in any case (Berzins & Loveday 1999, p. 2). However, the importance of post-school training, to improve the technical skills of the locals, had been recognised by the passage of the very first piece of legislation during the inaugural sitting of the Northern Territory Legislative Council in 1948. This ordnance provided for the establishment of the Apprenticeships Board. Vocational education and training was one of the few things the normally combative senior public servants and minority of elected members, who together comprised the Legislative Council, could agree upon.

This act allowed the first apprentices to become indentured to employers in 1949 (Urvett 1982). In the following year, approval was given by the Northern Territory Administrator to offer to Alice Springs residents ‘evening continuation classes’ from South Australia and, in 1951, for supervised study classes to enrol apprentices as well as clerical, French and public service examination preparation courses being made generally available in Darwin (Berzins & Loveday 1999). Apprenticeship trade training was carried out in the various workshops of the NT Administration and theory lessons were provided by correspondence from interstate. The numbers of apprentices were minimal with 33 apprentices in eight trades in 1953. This grew to 79 apprentices (with 15 being located in Alice Springs) in ten declared trades by 1958-59 (Berzins & Loveday 1999). In the years 1957 to 1959, the numbers of enrolments in the adult education centres grew rapidly. In Darwin they went from 482 students in 16 classes to 948 in 48 classes while in Alice Springs enrolments grew from 129 to 198 in 13 classes (National Archives of Australia 1961).

For Indigenous people, the training function of the various missions was progressively being more directly controlled by the Commonwealth Government throughout the 1950s. By 1956, the NT Administration’s Welfare Branch had assumed responsibility for education and training in order to achieve the major policy goal of assimilation (Hart 1970; Minister for Territories 1958). The unequivocal intention was to train Indigenous people for suitable employment and to establish their place in appropriate industries. The role of the missions and settlements that had been created post-World War Two, mainly outside the Top End, had been reconceived by the Commonwealth Government. They were primarily regarded as training centres facilitating social and economic change that would replace the Indigenous traditional lifestyle with the need to work in order to buy food and other things (Working party on vocational training for Aboriginals in the Northern Territory 1973). The program of assimilation operated on a broad front with training courses for hygiene assistants being conducted at Bagot and Amoonguna from 1952 and ranging to the operations of a Central Training Establishment in Darwin in 1959 to organise training for Indigenous people living away from home.

In 1957, the appointment of part-time registrars allowed for the opening of Adult Education Centres in Alice Springs and Darwin. A full-time principal was appointed in Darwin in March 1959 operating from the Darwin Upper Primary School in Wood Street. Given that the first secondary school in Darwin was closed in 1948 due to a lack of students and that Darwin High School would not open until 1963 at Bullocky Point, these buildings represented the epitome of education and training in the Top End at the end of the decade.

In spite of the broad acceptance of the role of vocational education and training as an important mechanism for the improvement of the Northern Territory, one consistent characteristic of the training sector has been evident from its very inception. The control of training policy and funding has always been contested by the various interest groups that seek to enhance the lives of others. From the end of World War Two until the early 1970s, education services were provided in the Northern Territory by South Australian Government agencies under contract to the Commonwealth Government. The provision of adult education in South Australia, and hence the Northern Territory, was dogged by a battle for control that was being fought between the University of Adelaide, that would eventually move away from the sector twenty years later, and the South Australian Education Department. This department redesignated its country technical high schools as ‘adult education centres’ in 1957 and planned for a wide expansion of adult education, including in the Northern Territory (Alexander 1959, p. 24-25). The enduring disputes and quarrels over the command of vocational education and training have proven to be an important feature of every decade’s story.

The 1950s marked the start of the transition to a more secular and wide-spread desire to economically and socially develop the entire Northern Territory population. For example, the Baptist missionaries that came to the government settlements at places like Yuendumu, Lajamanu and Ali Curung gave higher priority to developing a culturally appropriate gospel and providing services additional to those supplied by the Welfare Branch than in the direct provision of training (Jordan 1999). Through a variety of bureaucratic and legislative tactics, the Commonwealth Government forced the missionaries to share their deployment of training as an Indigenous-specific project of economic improvement. This transition was also accompanied by a shift in the funding source for much of the training that had taken place in the Northern Territory. Private donations and philanthropy were being replaced by taxpayer’s dollars.

Apprenticeships and adult education: the 1960s

Despite a confidential memo to the Prime Minister from the Minister for Territories, the Menzies Government remained generally disinterested in the development of the north of continent (Hasluck 1963). His submission dealt with some familiar themes such as the need for cross-border cooperation to promote northern advancement, the development of an oil refinery and the potential of tourism as an emerging industry. These could be used to encourage private investment in the Northern Territory and government could further assist by decentralising more functions away from Canberra and increasing public spending on critical infrastructure projects. In spite of the minister’s personal interest and optimistic demeanour, the Commonwealth still treated the Territory as a colonial backwater throughout the 1960s.

Following the end of World War Two there was a massive effort made to establish an Australian manufacturing industry base and a general shift of economic development policy away from rural enterprise towards ensuring a reliable industrial workforce housed in prosperous metropolitan areas (Butlin, Barnard & Pincus 1982). In addition, there was a continual national neglect of technical and further education through this decade with funding being diverted to schools and universities (Butlin, Barnard & Pincus 1982). The Commonwealth Government saw little benefit from prioritising the economic development of the remote northern colony by diverting southern urban funding or developing the human capital in a jurisdiction that did not even have the right to vote in elections.

The various Commonwealth Ministers, Administrators and their NT Administration remained firmly in control of virtually every aspect of the residents’ lives during this period. In a well-practised response to local demands for increasing the skills and knowledge of Territorians, three major inquiries into education and training matters took place in the 1960s (National Archives of Australia 2014).

The first was established in 1960 by Minister Hasluck and was conducted by three senior bureaucrats who received written submissions and conducted public hearings in the larger population centres. In total, 78 persons gave evidence to the committee and at least nine written submissions were received. In his submission to the inquiry, the senior psychologist of the South Australian Education Department advocated for the establishment of technical high schools in the Northern Territory in order to supply skilled tradesmen to support an emerging economy.

These schools could also make special provisions for ‘slow learning children and part-Aboriginal children, as well as dull whites who are incapable of working beyond semi-skilled levels’ (National Archives of Australia 1961). Another submission called for the setting up of ‘an agricultural college to assist with the development of the Territory and afford Asiatic students facilities for training’ (National Archives of Australia 1961). The inquiry’s major recommendation called for a decade-long process of transferring responsibility for education and training from South Australia to the Northern Territory.

The elected members of the Northern Territory Legislative Council (1962) held an inquiry into the educational needs of Territorians and published their rather limited findings in 1962. They found that the provision of post-primary education was incomplete and noted a lack of demand for technical training in spite of preliminary planning for the establishment of a technical high school at Bullocky Point in Darwin having been completed. The committee also expressed a preference to have local control over all aspects of education and training rather than relying upon the administrative arrangements that saw all major decisions being made in Adelaide by the South Australian Education Department.

The third inquiry’s findings, known as the Watts-Gallacher report, paid specific attention to education and training for the Territory’s Indigenous population (Northern Territory Archives Service 1964). The overarching policy goal of assimilation was still guiding the proposals contained in this report. Vocational education and training was singled out as being of ‘vital importance’ to social progress and the assimilation program. Training was being provided by over 40 adult educators who were located in the various missions and settlements in 1964.

The transition from missionary endeavours to government control and funding of vocational training that had commenced in the previous decade continued throughout the 1960s. Public subsidies were paid to support the work of the missions and some of these funds were used to pay minimal wages to Indigenous workers. The Methodist missions in Arnhem Land established formal apprenticeship schemes from 1962 onwards to train fitters and turners, motor mechanics, electricians, carpenters and joiners, boat builders and cabinet-makers.

These schemes were significantly expanded throughout the decade is response to major increases in the government subsidies. Many remote Indigenous people completed teaching and nursing training courses in Darwin following basic training in their communities (Baker 2012).

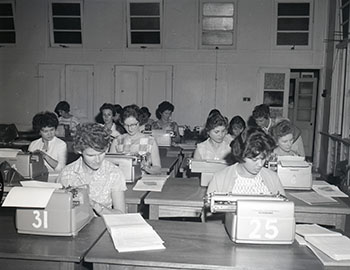

Adult Education Centre,Woods Street, Darwin. Typing class

For the rest of the population not living on settlements or missions, additional adult education centres opened in Batchelor, Katherine and Tennant Creek between 1963 and 1966. By the end of the decade enrolments in the Darwin Adult Education Centre reached about 5000 and were approaching 1000 in Alice Springs (Urvett, Heatley & Alcorta 1980). Due to the heavy workload experienced by the Darwin-based principal in 1969, the Alice Springs Adult Education Centre was returned to the South Australian control until 1974.

In 1967 the South Australian Education department appointed three trade teachers to positions at the Darwin Adult Education Centre to teach ‘attendance classes’ for apprentices in the automotive, electrical, carpentry and joinery trades. With the support provided by the NT’s first off-the-job trainers, the number of apprentices quickly doubled with 269 in training by 1971 (Wilson & Estbergs 1984).

In addition, a teacher assistant course was established at the Darwin-based secondary boarding school for remote Indigenous students, Kormilda College, in 1968. This would prove to be the foundation for the development of Batchelor College (Uibo 1993), building upon the small scale training centre for Indigenous people that had been established at Batchelor in the late 1960s in the abandoned facilities of the Atomic Energy Commission (Working party on vocational training for Aboriginals in the Northern Territory 1973). When the Uniting Church created the Institute for Aboriginal Development in Alice Springs in 1969, a new movement aimed at filling the vocational training aspirations of adult Territorians commenced and it would be the dominant feature of the decade that was to follow.

The major training policy trends that had been formulated in the previous decade continued along a similar trajectory throughout the 1960s. However, the growing population, the absence of post-school options similar to the other jurisdictions and the calls for more local control of funding and decision-making in education and training were becoming too hard to ignore.

The communities’ colleges: the 1970s

Aerial view, Darwin Community College, with Alawa behind

At the start of the new decade, the Darwin Adult Education Centre remained as the only post-school option for education and training for residents of the Top End. In addition to Darwin, the centre had branches in Nhulunbuy, Katherine and Alyangula each with a range of part-time staff teaching locally relevant coursework. The main centre had six senior staff, 16 full-time teachers, seven ancillary staff and 160 part-time teachers. Alice Springs and Tennant Creek were still being catered for through the South Australian Education Department’s adult education programs.

As the Territory’s population continued to grow quite rapidly, The Commonwealth had been progressively returning electoral rights to the jurisdiction and those who were elected to represent Northern Territory interests continually pressed for greater levels of local control in all areas including education and training. Various federal government agencies were also showing an increased interest in pursuing their own agendas in what many came to believe was akin to treating the Territory as a ‘social laboratory’.

June 1973, there were 360 registered apprentices in 38 declared vocations in the NT, representing an increase of 80 from the previous year. Adult education in remote communities included subjects in carpentry, mechanics, sewing, English literacy, general education, mother’s club, music, pottery and health/nutrition (Department of Education: Northern Territory Division 1974).

By the end of 1972, responsibility for education and training was being progressively relinquished by South Australia and taken over by the Commonwealth Department of Education - NT Division (Urvett 1982). As part of this transition, the Commonwealth had finally agreed to establish and furnish facilities for the Northern Territory’s first tertiary education institution (Darwin Community College Planning Committee 1970). Unlike other jurisdictions, the NT would be home to Australia’s first community colleges, an idea imported from North America. The Darwin Community College opened in March of 1974 and this new organisation would also assume operational responsibility for an Alice Springs Community College. Both organisations incorporated the functions of the former adult education centres.

In Alice Springs, the new college would continue to operate out of the original high school at Anzac Hill while in Darwin a greenfields site was progressively being established at Brinkin, only to be severely damaged by Cyclone Tracy only months after its official opening. Non-award courses were also offered in Katherine, Nhulunbuy, Pine Creek, Batchelor, Alyangula and Tennant Creek (as an annexe of Alice Springs). During 1974, the number of Darwin Community College lecturers increased from 53 to 68 and the number of other staff went from 36 to 71 in order to cater for well over 4000 students, many more than anticipated (Berzins & Loveday 1999).

The theme of increased levels of local control and advice not only dominated the relationship between the elected members of the NT Legislative Council (to be replaced by the Legislative Assembly in 1974), but it was also an important matter for the various regions and population groups that made up the Territory. Many groups, each with their own agendas of improvement, staked a claim to training and the result was a proliferation of community-based institutions that were reliant upon public funding. In addition to the two community colleges, Batchelor College and Nungalinya colleges were established in 1974, the same year as the Technical and Further Education sector, universally known as TAFE, came into existence and started attracting significant national funding.

Agitation for more local control of training throughout the decade saw the establishment of the Katherine Rural College in 1979 (Katherine Rural College Planning Committee 1976) and the Community College of Central Australia in Alice Springs. These two would join renamed Batchelor College of TAFE in being responsible, through their councils, to the NT Education Department and Minister for Education as a result of the report of the Education Advisory Group (1978). This body had been formed by the new ‘self-governing’ Northern Territory’s Cabinet to recommend on how to best govern education and training in preparation for the handover of the responsibility for TAFE from the Commonwealth Government in mid-1979.

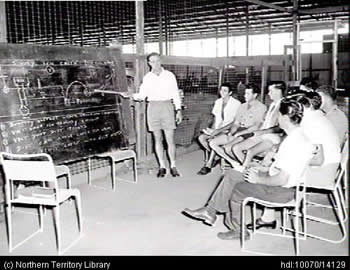

David Handley, first year apprentice and Robert Scott,

Trades Foreman, during an apprentice training session.

In yet another recurring theme, the long-desired capacity to have advanced and higher education courses offered by a local institution in the Northern Territory was inextricably built upon the foundation of the vocational training sector. And the contests for control over the policies, funding and program priorities would continue to rage over the decades to follow.

In only its 14th decision, in 1977 the newly formed NT Cabinet decided to move the Apprenticeships Board out of the Department of Education (Northern Territory Archives Service 1977-2003a) in response to continual antagonism between the business and industry representatives of the board and the educationalists of the department (Department of Education: Northern Territory Division 1977). In addition, the bureaucrats of the NT Education Division and the senior academics at the Darwin Community College had argued strongly against the responsibility for education and training being transferred to a self-governing Northern Territory (Northern Territory Archives Service 1974-1987) while the members of the Apprenticeships Board were supportive of local political ambitions. In June 1977 there were 869 apprentices in 51 declared vocations.

By the end of the 1970s, the Northern Territory had achieved self-government and local control of education and training driven by generous financial arrangements with the Commonwealth (Heatley 1990). This had also been accompanied by an end to the assimilationist policies aimed at Indigenous Territorians and a shift to programs aimed at integration, self-determination and self-management conceived of as being the rights of an Australian citizen. Vocational training was also seen as a vital part of these new policies as well as an important contributor to the economic development of a newly confident territory that could chart much of its own future.

Adversaries, administration and acronyms: the 1980s

Crowd at opening of Territory Training Centre Building was formerly

power station. Armidale Street, Stuart Park, Darwin

The 1980s finally saw the control of TAFE now firmly in the hands of Territorians. As in the past, many groups sought to direct both the policy and funding decisions of the sector. In one of the early decisions taken by the NT Government, the NT Industry Training Commission replaced the Apprenticeships Board in June 1980. There were 1007 apprentices registered in June 1981 and 21 declared trades involved the use interstate training for off-the-job components (Northern Territory Industry Training Commission 1981).

This would be only the first of the decade’s many changes in administrative arrangements that would result in a total of two commissions, four different government departments and one institute being given various amounts of discretion over policy and funding for the training sector. The functions of each of these bureaucratic organisations were always supplemented by arrangements for the provision of advice, generally justified on the grounds that business and industry needed to have a major voice in determining the direction of training policy and programs. The 1980s featured the Post-School Advisory Council, the TAFE Advisory Council, five Industry Training Committees, the Industry and Employment Advisory Council and, finally, the Aboriginal Training and Employment Board of Management.

These were in addition to the various college councils that had responsibility for the operations of the main training providers in the NT and provision of advice to the Education minister. Each of these bodies was also designated its own acronym and the use of these contractions would become endemic in the sector. A number of important participants in the battles for control of the sector have commented upon the ability of certain experts to use acronyms as ‘tools of obfuscation’ and as an ‘unintelligible foreign language’.

The NT Government decided to intervene directly in the training of apprentices in 1980 by establishing the Skills Training Centre in the former powerhouse in Stuart Park (Northern Territory Archives Service 1977-2003b). This increased provision of training for trade apprentices was done because the Darwin Community College was operating at full capacity, government agencies were constrained by strict enforcement of staffing establishment positions and there were substantial federal government funding grants available. There were 1231 apprentices in training June 1984 (Northern Territory Vocational Training Commission 1984).

In 1985 the Northern Territory Government also adopted the new national category of traineeships in order to address growing numbers of unemployed youth. The numbers of students in traineeships would eventually grow to out-number traditional apprentices. In 1989 Group Training Companies were opened in Alice Springs and Darwin to offer ongoing employment for apprentices in industries that could not guarantee a position over the three or four years required to complete the formal training.

The self-governing Northern Territory also had permanent plans for a local university in order to have all of the trappings of a modern state (Harris 1985). The fate of vocational education and training was always tied to the establishment of a university in the Territory. Several major decisions were made by the NT Government in pursuit of this goal. These included converting the Darwin Community College to the Darwin Institute of Technology in 1984, creating the University College of the Northern Territory in 1985 (in spite of fierce opposition from the Commonwealth Government) and finally opening the Northern Territory University in 1989 as a result of amalgamating the institute and university college.

The new university had an Institute of TAFE with its own board of directors. One of the policy decisions that supported the establishment of the university categorically rejected any bid from Central Australia to offer higher education in the region and the name of the community college was changed to the Alice Springs College of TAFE in 1987 to reinforce the role assigned to that organisation (Northern Territory Archives Service 1980-1982).

Improving the lives of Indigenous Territorians also remained an important consideration for Government in planning for how to use vocational education and training. In May 1980, the NT Cabinet made a major policy decision to adopt community development principles of self-management and self-determination for Aboriginal communities (Northern Territory Archives Service 1980). It was recognised that community members would require increased skills to progressively operate, under contract, most government functions in their local areas. Vocational education, in general, and the specific role of adult educators were singled out as being crucial to the success of this new approach to Aboriginal affairs (Loveday & Young 1984; Strike 1981). Over the decade several new administrative arrangements were put in place to support the integrated development of Aboriginal self-realisation. These included establishing the NT Open College in 1986 and establishing Community Education Centres in a number of remote communities commencing in 1988 (Northern Territory Open College 1987). Both of these initiatives were dogged by the same battles over control with adult educators being caught between answering both to local school principals and senior Open College managers located in major population centres. In spite of these organisational skirmishes, the NT received national recognition for pioneering a number of flexible delivery strategies, including mobile workshops, to provide greater access to training.

In response to the low numbers of Indigenous students enrolled in formal training programs in Central Australia, the Centre for Appropriate Technology was opened in 1980. It would progressively gain its independence from the community college and pursue its own path by providing culturally appropriate training under the guidance of its own Indigenous board of directors. Another response was the establishment of the Alice Springs campus of the Batchelor College of TAFE commencing in late 1989.

By the end of the 1980s, the constant organisational/advisory changes and endless bureaucratic wrangling over the acronym-saturated vocational education and training sector had set the scene for an era of comparative administrative stability. The Northern Territory, like every other state, was having to respond to a much larger national agenda and became a leader in developing most of the elements of the national training system that would emerge in the 1990s. In order to focus resources upon its relationship with the Commonwealth Government (and its superior financial resources), the Northern Territory Cabinet decided to take the control of policy and funding out of the hands of senior public servants and give it to an independent body.

Authorities and additional advice: the 1990s

The new decade would usher in a new acronym for the vocational education and training sector - VET. The former generic name, TAFE, would be reserved for the state-owned and operating training bureaucracies while VET would encompass public, private and enterprise training providers operating in a more market-driven funding environment. The long-desired goal of having a national training system would also come to fruition and the Northern Territory played a leading role by being the first jurisdiction to introduce competency based training into apprenticeships and traineeships.

In addition, the NT also replaced ‘time-served’ on the job training with a system that recognised the ‘skills demonstrated’. Like the other states, the Territory also rejected the 1992 attempts by the Commonwealth to take control of VET as had been done in higher education (Goozee 2001). VET is, quite simply, too useful as a public policy response to be relinquished to another government.

In the time-honoured practice, the decade commenced with a review of the industries and employment training legislation in 1990 (Northern Territory Archives Service 1984-1991). This was done in response to string representations on the part of business and industry leaders seeking to have more direct impact in the sector and its priorities. Deficiencies with the first review prompted a second review that allowed for the elimination of the continual bickering between government agencies over the control of vocational education and training. The decision was taken by the NT Government in 1990 to establish the NT Employment and Training Authority and legislation was passed in 1991 allowing its operations to commence in January 1992 (Northern Territory TAFE Advisory Council 1992).

The establishment of NTETA also anticipated the creation of the Australian National Training Authority and its stewardship of the emerging national training system. As in the previous decade, the proliferation of acronyms and advisory arrangements grew at phenomenal rate in the 1990s. Again, the Northern Territory led the nation in the reform of the VET sector and was well positioned to take advantage of national programs and initiatives (Industry Commission 1998; Martin & Dewar 2012).

Of particular importance was absence of a public TAFE system in the Northern Territory. Unlike their counterparts in other states, NT ministers were not hampered by conflicts of interests associated with policy decisions for the creation of a contestable training market while having to consider the operational issues of running their own training system. Delivery of VET in the NT was ‘outsourced’ to an increasingly varied group of registered training organisations (Zoellner 2013).

At the start of the 1990s, the newly established training authority dealt with four private training providers operating in the NT: GEMCO on Groote Eylandt, Ranger Mines at Jabiru, Nabalco at Gove and Nungalinya College in Darwin (Northern Territory TAFE Advisory Council 1992). The major public providers included Batchelor College of TAFE, the NT Open College, the NT Rural College, the Alice Springs College of TAFE (all operating under the Education Act) and the Institute of TAFE at the NT University. In addition, both the Institute for Aboriginal Development and the Centre for Appropriate Technology were active in Central Australia.

There were 1257 apprentices and 162 trainees registered in June 1990 (Industry and Employment Advisory Council 1990). This number of people in training had remained quite constant throughout the second half of the previous decade (Northern Territory of Australia 1989). By the end of 1992, the number of private training providers in the NT had grown to 14 (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 1993).

The providers of training continued to evolve in response to community priorities and ministerial direction. Following an extensive process of consultation, the logic of dual-sector education and training provision was extended in Alice Springs with the creation of Centralian College which incorporated the former Sadadeen Senior College and the Alice Springs College of TAFE in 1993. In the following year, many of the functions of the NT Open College were transferred to Centralian College and the NT University (Finch 1993).

Group Training NT was formed when Top End Group Training absorbed the operations of the Central Australian organisation in 1996. In support of Aboriginal self-realisation for the provision of higher education in a dual-sector organisation, the Batchelor College was redesignated as the Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education in 1999 (Manzie 1999). Yet again, the future of higher education provision was being built on the back of vocational education and training.

The creation of NTETA addressed two major issues. The first provided for a unified NT position in dealings with the increasingly powerful ANTA and this was informed by the second matter, giving business and industry the major voice in training policy and public funding allocation in support of improving the skills of Territorians and meeting the labour market demands of the private sector.

NTETA’s consultative mechanisms were large, highly inclusive and complex. There were initially four Advisory Councils each chaired by a member of the NTETA Board. Between them they had over 40 individuals representing virtually every interest group in the NT (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 1993). There were also a Women in TAFE Committee and a Women’s Reference Group (Northern Territory Department of Education 1993).

Also adding to the depth of industry participation, there were 12 Industry Training Advisory Boards that were tasked with the development of industry-specific training plans. This number would be reduced to 11 in 1995 and they looked after 98 different declared vocations (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 1996). More than 200 individuals were directly involved in the provision of advice to NTETA.

1991 - Apprentices at HOD Diesel Plant

By the end of the 1990s, NTETA had reduced the number of advisory councils to three and dealt with 107 registered training organisation operating in some 109 declared vocations (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 1999). In the final years of NTETA’s existence, its apprentice support services were outsourced to a joint NT-Commonwealth Apprenticeship Centre in 1998 (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 1999) while the number of industry advisory boards was reduced to 6 Training Advisory Councils in 2001 (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 2001).

While the VET sector was dominated by NTETA in the 1990s, the start of the next decade ushered in the use-by date for the authority structure. There were plans by the existing government to convert NTETA into a Department of Employment and Training and the change of government in the 2001 NT election only hastened the return of VET policy and funding to government departments.

NTETA and ANTA and their implementation of the national training system had seen a massive growth in the provision of formal training. In the Northern Territory the number of students enrolled in VET courses increased from 8800 in 1990 to more than 19 100 in 1999 which was greater than the number of vocational students in the Australian Capital Territory (National Centre for Vocational Education Research 2014). They were being trained in 79 registered training organisations and this total number included 2161 apprentices and trainees in 1999 (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 2000).

Return to the departments and consolidation: the 2000s

In 2001, the major functions of NTETA were progressively transferred to a newly created Department of Employment, Education and Training. Yet again, the NT was leading the training policy agenda as the Commonwealth would abolish ANTA and transfer its functions to a department from July 2005. The NT department found itself providing funding for 2494 apprentices and trainees in 130 registered training organisations in 2001 (Northern Territory Department of Employment 2002).

In its final year of existence, NTETA had purchased training and related services to the value of $65 million with 40 per cent going to the NT University, 13 per cent to Batchelor Institute, 12 per cent to Centralian College, other providers receiving 20 per cent and the remaining 15 per cent being used to fund ‘user choice’ training for apprentices and trainees (Northern Territory Employment and Training Authority 2001).

The massive advisory infrastructure of NTETA was replaced initially by a Ministerial Advisory Board for Employment and Training in 2002-03 and this group was, in turn, replaced by Ministerial Roundtables held in the major population centres for a couple of years dating from 2006.

By the end of the decade, there were no formal advisory groups in existence except for the six Training Advisory Councils, confirmed in 2003, looking after their specific industry groups. The provision of policy and funding priorities for vocational education and training was back in the hands of technical experts and senior public servants. It did not take long for the battles for control of the sector that had dominated the 1980s to re-emerge amongst those who wished to further improve the Territory. Business and industry, in particular, were highly critical of the single agency approach and eventually the employment function was transferred to a new Department of Business and Employment in 2008.

The provision of training would see a consolidation of the public providers into two organisations. Batchelor Institute retained its independence in spite of continued speculation about its future and its eventual partnership with the university to operate the Australian Centre for Indigenous Knowledges and Education. In 2001, the operations of the Katherine Rural College were incorporated into the NT University. Following a major process of community consultation and negotiations with the Commonwealth Government, Charles Darwin University was created by the formal merger of the NT University, the Katherine Rural College, Centralian College and the Menzies School of Health Research in 2003. Both of these dual-sector training providers continued to operate in the quasi-training market that was funded and monitored by the Department of Employment, Education and Training. 2003 also saw the establishment of Desert Knowledge Australia in its own dedicated precinct on the outskirts of Alice Springs.

Federal political ambitions in pursuit of their own plans for improving the Northern Territory through the use of vocational education and training re-emerged in 2007 with creation of the Australian Technical College in Darwin. This constitutionally bold and administratively top-heavy intrusion into the NT training environment was ended rather abruptly in 2009 when the functions of the technical college were absorbed into the NT Department of Education and Training following the redirection of this funding to Trade Training Centres in schools by the recently elected Australian Government. This was followed by the establishment of a VET in Schools Group in the Department of Education and Training in 2010.

Just as the belief in industry control of vocational education and training had guided the authority structure of the previous decade, the public policy environment of the 2000s was directed by the belief that government departments headed by politically astute public servants responsible to elected ministers would provide the best means of improving the social and economic prospects of the Northern Territory. The balance between these two policy positions would shift yet again in the next era.

Back to the future: the 2010s

The official opening of the Desert Peoples Centre in the Desert Knowledge Australia precinct in 2010 marked the culmination of a process of planning that had commenced in 1998 when Batchelor College, the Centre for Appropriate Technology and the Institute for Aboriginal Development formed a consortium to further Indigenous self-determination (Ramsey 2002).

As always, the use of vocational education and training policy and funding programs was characterised by disagreements over control. The Institute for Aboriginal Development pulled out of the project to develop the Desert Peoples Centre in order to invest $2.6 million of ANTA capital works funding it controlled on its own campus. The decision in 1980 to improve the lives of Indigenous Territorians through self-management and community development initiatives was still a guiding policy in the contemporary decade.

The pressure on the NT Government to increase the amount of business and industry influence in vocational education and training was being advanced by local interests as well as national policy settings that had been agreed through a series of national partnership agreements. In 2011, the decision was taken to remove the non-schools-based training functions from the Education Department yet again and reposition them in the Department of Business and Employment (Knight 2011).

With the change of NT Government in 2012, the Department of Business retained responsibility for both employment and training policy and funding programs. As one of its pre-election commitments to re-assert business and industry control over the sector, the new government established a NTETA Advisory Board in 2013. Under the auspices of this group reviews of the employment and training act and funding models that support training have been conducted as well.

In 2010-11, there were 4100 apprentices and trainees as part of the 24 000 Territorians enrolled in vocational education and training (Northern Territory Department of Education and Training 2012). By the middle of the decade, the total number people in training is 25 100 which is being delivered by about 50 Northern Territory-based registered training organisations and a smaller number of interstate providers.

Charles Darwin University remains the largest provider of training with about 12 000 students undertaking 2.8 million hours of training. Of this number, about 28 per cent of students identify as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. In 2013, the NT Government funded 16 600 students for training delivered by the two public providers and 6300 students from other training organisations, in other words, about 38 per cent of the publicly funded NT training market was conducted by private or not-for-profit providers.

Vocational education and training policy remains an important tool for politicians, bureaucrats and business leaders. Its history in the Northern Territory is characterised by continual struggles for control of the sector and who pays for its operations. VET has had many uses and can be reconfigured to meet almost any policy objective.

This was amply demonstrated that training could be on one hand the vital component of assimilation or, on the other hand, the major contributor to self-determination. VET was also used in the Territory to build the university and support aspirations for an Indigenous university. No matter how it is used, it is all but impossible to find someone who will speak against using vocational education and training because everyone ‘knows’ that it is a good thing.

Give feedback about this page.

Share this page:

URL copied!